Introduction

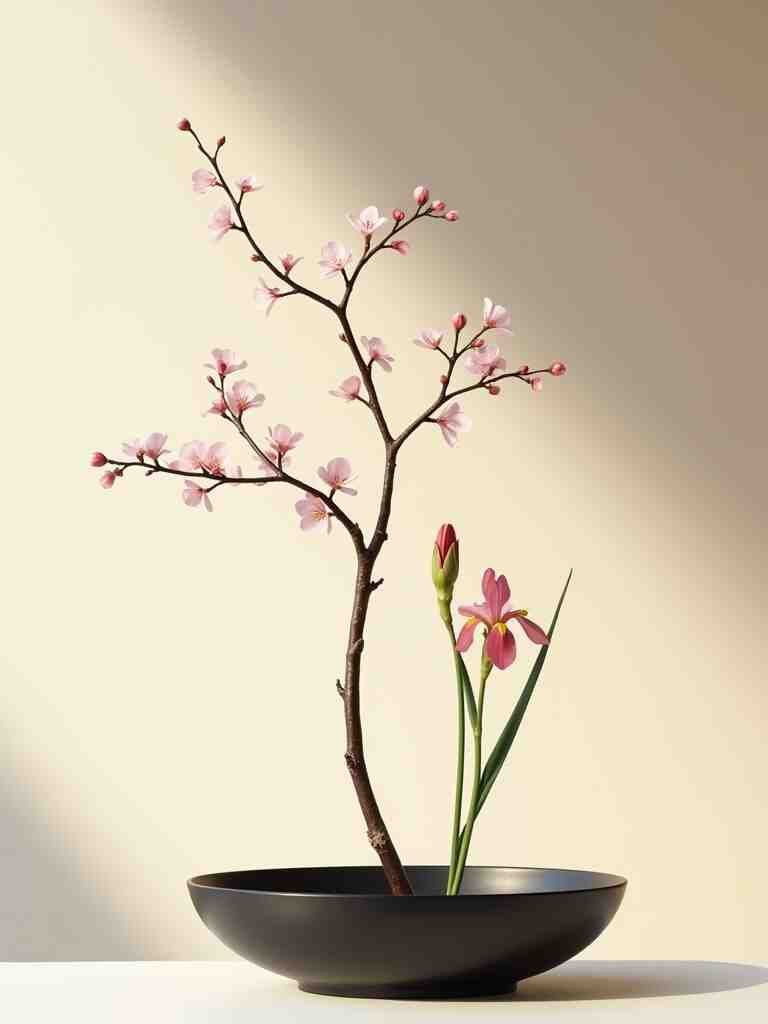

Japanese Art of Flower arranging nyt ( Ikebana ) represents one of Japan’s most elegant cultural expressions capturing the essence of natural beauty through mindful flower arrangement. This ancient practice dating back over 600 years transcends simple decoration evolving into a spiritual discipline that celebrates the harmony between humans and nature. Today this art form continues to captivate enthusiasts worldwide appearing frequently in publications like The New York Times and challenging puzzlers in crosswords. This exploration reveals the rich traditions techniques and philosophy behind the Japanese art of flower arranging.

The Historical Roots of Ikebana

Ancient Origins and Buddhist Influence

The story of ikebana begins in sixth-century Japan when Buddhist monks from China introduced flower-offering rituals. These early arrangements placed at temple altars represented spiritual devotion rather than mere aesthetic displays. The earliest recorded ikebana arrangements appeared during the Heian period (794-1185) where nobility would place seasonal branches and blossoms in shallow vessels as offerings.

Buddhist priests particularly those of the Ikenobo school established the first formal ikebana styles. These priests living near Kyoto’s Lake Biwa crafted arrangements that reflected Buddhist principles of impermanence harmony and respect for all living things. The practice gained its name from “ikeru” (to arrange) and “hana” (flowers) though early practitioners called it “tatehana” meaning “standing flowers.”

Evolution Through Japanese History

During the Muromachi period (1336-1573) ikebana evolved from strictly religious practice to artistic pursuit. The influential treatise “Sendensho” written in the mid-15th century codified early ikebana principles establishing it as a distinct art form with philosophical underpinnings.

The Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573-1603) saw ikebana reach new heights through the patronage of powerful warlords including Toyotomi Hideyoshi. The tearoom (chashitsu) became an important venue for displaying flower arrangements leading to the development of chabana (tea flowers)—simple arrangements that complemented the austere tea ceremony aesthetic.

By the Edo period (1603-1868) Japanese Art of Flower arranging nyt ( Ikebana ) had spread beyond temples and aristocratic circles becoming accessible to merchants and commoners. This democratization led to numerous schools and styles developing throughout Japan each with distinctive approaches and philosophies.

Major Ikebana Schools and Their Philosophies

Ikenobo: The Oldest Tradition

Founded in the 15th century the Ikenobo school remains the oldest and most traditional ikebana lineage. Rooted in Buddhist temple traditions Ikenobo emphasizes formal structure and precise technical execution. Two primary styles characterize Ikenobo arrangements:

Rikka (Standing Flowers) – The original formal style representing idealized landscapes with seven to nine principal branches symbolizing elements of nature like mountains valleys and waterfalls. Rikka arrangements express the magnificence of nature through strict adherence to rules regarding placement angle and depth.

Shoka (Living Flowers) – A simplified form developed in the 17th century focusing on three main branches: shin (truth/heaven) soe (supporting/human) and tai (body/earth). Shoka arrangements celebrate the essential characteristics of plants through minimalist expression.

Sogetsu: Modern Creative Expression

Founded in 1927 by Sofu Teshigahara the Sogetsu school revolutionized ikebana by introducing avant-garde concepts and materials. With its motto “Japanese Art of Flower arranging nyt ( Ikebana ) can be arranged anytime anywhere by anyone with any material” Sogetsu embraces creative freedom while maintaining respect for traditional principles.

Sogetsu practitioners often incorporate unconventional materials like metal plastic or found objects alongside plant materials. The school encourages personal expression viewing ikebana as sculptural art that can adapt to contemporary spaces and sensibilities while still honoring spatial awareness and the inherent qualities of materials.

Ohara: Bridging Traditional and Modern

Established in the late 19th century by Unshin Ohara the Ohara school developed partly in response to Western influences entering Japan. Its signature style moribana (piled-up flowers) introduced the shallow circular container (suiban) allowing flowers to be arranged in naturalistic landscapes rather than strict vertical compositions.

Ohara school specializes in representing natural scenery through careful placement of seasonal materials. Their landscape arrangements (known as landscape moribana) showcase seasonal environments like mountain streams autumn fields or spring gardens with remarkable accuracy.

Other Notable Schools

Chiko School – Founded in the Edo period emphasizes seasonal awareness and naturalness focusing on expressing the character of each season through appropriate materials and arrangements.

Saga Goryu – Connected to the imperial court in Kyoto this school maintains highly formalized styles associated with aristocratic traditions.

Enshu School – Founded by tea master Kobori Enshu known for simple elegant arrangements that complement traditional tea ceremony aesthetics.

Fundamental Principles of Japanese Art of Flower arranging nyt ( Ikebana )

Three Main Lines: The Structural Foundation

At the heart of most ikebana arrangements lies a triangular structure formed by three main lines:

Shin (Truth/Heaven) – The tallest vertical line representing the connection between earth and heaven traditionally 1.5 to 2 times the height of the container.

Soe (Supporting/Human) – The secondary line typically positioned at about 75% the length of shin usually angled at 45 degrees representing human existence.

Tai (Body/Earth) – The shortest line often positioned at the front representing earth and positioned at 45 degrees in the opposite direction from soe.

These three lines establish the primary structure creating a three-dimensional triangular space that forms the skeleton of the arrangement. The precise positioning varies by school and style but the concept of asymmetrical balance through these three lines remains fundamental.

Negative Space: The Power of Ma

Perhaps the most distinctive aspect of ikebana compared to Western flower arrangement is its emphasis on negative space known as “ma” in Japanese aesthetics. This concept refers to the meaningful empty spaces between elements that are as important as the materials themselves.

Skilled Japanese Art of Flower arranging nyt ( Ikebana ) artists carefully consider how spaces between branches flowers and leaves create tension balance and visual interest. Rather than filling space ikebana practitioners sculpt it allowing viewers to experience both the presence of materials and the absence that defines them.

Asymmetry and Balance

Ikebana rejects perfect symmetry in favor of dynamic asymmetrical balance that reflects natural growth patterns. Arrangements typically feature odd numbers of elements (3 5 7) positioned at varying heights and angles creating visual interest without perfect mirroring.

This preference for asymmetry stems from Buddhist and Taoist influences which view perfect symmetry as artificial and static. The resulting compositions feel organic and alive with visual tension that draws the viewer’s eye through the arrangement.

Essential Elements and Materials

Traditional Containers (Utsuwa)

The container in ikebana serves as more than a vessel—it forms an integral part of the composition. Traditional containers include:

Suiban – Shallow circular or rectangular containers that hold water for moribana arrangements.

Nageire – Tall upright vases used for vertical arrangements often made of ceramic bamboo or bronze.

Kompai – Flat shallow plates used for low horizontal compositions.

Hanaire – Classic tall vases often with narrow openings made from ceramic bronze or bamboo.

The selection of container considers not only practical requirements but also season formality and thematic elements. A rustic earthenware pot might suit a wildflower arrangement while a refined bronze vessel complements more formal compositions.

Kenzan: The Hidden Foundation

The kenzan (literally “sword mountain”) serves as the mechanical foundation for many ikebana arrangements. This heavy metal plate covered in upright needles holds stems securely in precise positions. Properly using a kenzan requires skill—stems must be cut at sharp angles and inserted directly without repositioning which can damage plant material.

Alternative fixation methods include:

Kubari – Forked branches wedged inside containers to hold materials in place.

Mizukiri – Split bamboo sections used as grids inside containers.

Tsutsumi – Paper or leaf wrapping techniques that bundle materials together.

Seasonal Awareness and Material Selection

Japanese Art of Flower arranging nyt ( Ikebana ) strongly emphasizes seasonality (shiki) with arrangements showcasing materials that represent the current season. This temporal awareness connects arrangements to the natural world’s rhythms:

Spring – Cherry blossoms (sakura) plum blossoms (ume) narcissus and early spring branches with buds.

Summer – Iris hydrangea lotus and lush foliage representing vitality and growth.

Autumn – Chrysanthemums maple branches with colored leaves and grasses with seedheads.

Winter – Pine branches camellias winter jasmine and dormant branches showcasing essential forms.

Beyond flowers Japanese Art of Flower arranging nyt ( Ikebana ) incorporates branches grasses seedpods fruits vegetables and even dried materials. Each element selected not merely for color but for its line texture growth pattern and symbolic associations.

Core Techniques and Skills

Proper Cutting and Preparation

Successful ikebana begins with proper material preparation. Practitioners employ specific cutting techniques to maximize water uptake and achieve desired positioning:

Mizukiri (Water Cut) – Cutting stems underwater to prevent air embolisms that block water uptake.

Kegaki (Angled Cut) – Creating sharp diagonal cuts on stems to increase surface area for water absorption and facilitate proper placement in kenzan.

Hasami (Splitting) – Splitting woody stems at the bottom to increase water absorption and create stability.

Plants require conditioning before arrangement typically standing in deep water for several hours to ensure full hydration. Leaves that would sit below water level must be removed to prevent bacterial growth and foliage may require cleaning to remove dust or imperfections.

Balance and Proportion

Mastering proportion requires understanding the relationship between container materials and setting. Traditional guidelines suggest:

Height Relationships – The main shin branch typically measures 1.5-2 times the height plus width of the container.

Scale Consideration – Materials must suit the container size with larger vessels requiring more substantial materials.

Visual Weight – Balancing visually heavy elements (large flowers dense foliage) with lighter elements (slender branches delicate blooms).

Minimalism and Restraint

One defining characteristic of ikebana is its disciplined restraint. Unlike Western floral designs that may showcase abundance Japanese Art of Flower arranging nyt ( Ikebana ) practitioners select fewer materials focusing on quality over quantity. This minimalist approach:

- Highlights the essential character of each element

- Creates focused visual impact through careful selection

- Develops appreciation for subtle details and natural characteristics

- Removes distractions allowing viewers to contemplate individual elements

Learners often struggle with this restraint wanting to add “just one more flower” but mastery comes through understanding that power often lies in what is left out rather than what is included.

Philosophical Foundations of Ikebana

Zen Buddhist Influences

Zen Buddhism profoundly shaped ikebana development particularly during the 14th-16th centuries. Key Zen concepts embedded in Japanese Art of Flower arranging nyt ( Ikebana ) practice include:

Wabi-Sabi – Finding beauty in imperfection transience and simplicity often expressed through asymmetrical arrangements or materials with interesting “flaws.”

Mushin (No-Mind) – Achieving a meditative state while arranging allowing intuitive creativity to flow without overthinking.

Present-Moment Awareness – Focusing completely on the arrangement process as a form of moving meditation.

Many practitioners approach ikebana as spiritual practice rather than mere decoration finding that the focused attention required cultivates mindfulness and inner calm.

Relationship with Nature

Ikebana fundamentally expresses reverence for nature through several key principles:

Mitate (Seeing Anew) – Perceiving ordinary materials with fresh eyes discovering extraordinary beauty in common elements.

Respect for Natural Forms – Working with rather than against plant materials’ natural growth patterns.

Environmental Harmony – Creating arrangements that reflect natural ecosystems and relationships between elements.

Unlike some Western approaches that force materials into unnatural shapes ikebana seeks to reveal plants’ essential nature through thoughtful placement that respects inherent qualities. This approach reflects the broader Japanese aesthetic principle of working in harmony with nature rather than attempting to dominate it.

Symbolism and Meaning

Ikebana arrangements contain rich symbolic language understood by knowledgeable viewers:

Seasonal References – Materials that evoke specific times of year carrying cultural associations.

Buddhist Symbolism – Lotus representing enlightenment pine symbolizing longevity bamboo signifying resilience.

Directional Significance – East representing birth/spring south representing growth/summer west representing maturity/autumn and north representing retirement/winter.

Numerical Symbolism – Odd numbers considered dynamic and alive even numbers suggesting completeness or endings.

Historical arrangements often contained complex symbolic narratives understood by educated viewers much like visual poetry expressing ideas beyond mere decoration.

Modern Adaptations and Contemporary Practice

Global Spread and Western Influence

Following World War II ikebana gained international popularity through:

Cultural Exchange Programs – Japanese instructors traveled abroad establishing branches of major schools worldwide.

Western Adaptations – Modified approaches making ikebana accessible to practitioners without traditional Japanese cultural background.

Publications and Media Coverage – Books articles and features in publications like The New York Times introducing ikebana to Western audiences.

Today major ikebana schools maintain chapters throughout North America Europe Australia and Asia with international exhibitions and competitions showcasing global interpretations of this Japanese art form.

Innovative Materials and Approaches

Contemporary ikebana practitioners continually expand traditional boundaries:

Non-Traditional Materials – Incorporating wire metal plastic recycled materials paper and fabric alongside natural elements.

Environmental Awareness – Exploring sustainable practices including locally-sourced materials foraged elements and avoiding floral foam.

Cross-Disciplinary Approaches – Blending ikebana with installation art performance sculpture and other contemporary art forms.

Leading contemporary artists like Toshiro Kawase Akane Teshigahara and Misei Ishikawa balance tradition with innovation creating works that maintain ikebana’s essential principles while speaking to modern sensibilities.

Ikebana in Interior Design and Architecture

Contemporary designers increasingly incorporate ikebana principles into spatial design:

Architectural Integration – Purpose-built alcoves (tokonoma) in contemporary homes specifically designed for ikebana display.

Commercial Applications – Hotels restaurants and corporate spaces featuring rotating ikebana installations as signature design elements.

Spatial Awareness – Interior designers applying ikebana principles of asymmetry negative space and natural harmony to room layouts and furnishing arrangements.

Leading architects including Kengo Kuma and Tadao Ando have explicitly referenced ikebana’s spatial concepts as influences on their architectural approaches particularly regarding the meaningful use of negative space and asymmetrical balance.

Learning Ikebana: The Educational Path

Traditional Teaching Methods

Traditional ikebana education follows structured hierarchical approach:

Iemoto System – Headmaster-based teaching where knowledge passes through formal lineage with authority centralized in the family head.

Progressive Curriculum – Students begin with basic forms mastering fundamentals before advancing to more complex styles.

Certificate Levels – Formal recognition through testing and certification at progressive skill levels often with Japanese terminology and standardized requirements.

Most traditional schools require several years of study before students receive teaching credentials with mastery considered a lifelong pursuit rather than achievable endpoint.

Finding Instruction and Resources

Modern students can access ikebana education through multiple channels:

Local Chapters – Major schools maintain affiliated chapters worldwide offering regular classes for beginners through advanced levels.

Cultural Centers – Japanese cultural organizations and botanical gardens frequently host workshops and demonstrations.

Online Resources – Virtual classes video tutorials and social media communities connecting practitioners globally.

Books and Publications – Instructional texts ranging from beginner guides to advanced theoretical works available in multiple languages.

Serious students should consider whether they prefer traditional structured approach or more contemporary flexible learning as this significantly impacts the educational experience.

Practice Essentials for Beginners

New ikebana students should prepare:

Basic Tool Kit

- Sharp floral scissors (hasami)

- Small kenzan (needle holder)

- Simple containers (ceramic bowl shallow dish)

- Floral wire and tape for repairs

- Pruning shears for woody materials

Learning Environment

- Clean work surface at comfortable height

- Good lighting preferably natural

- Access to water source

- Space to view arrangement from multiple angles

- Reference materials showing basic forms

Beginning Practice

- Start with accessible materials like carnations chrysanthemums and easily-shaped branches

- Master basic three-line structure before attempting complex arrangements

- Photograph arrangements to track progress

- Practice regularly even with simple materials

Ikebana in Popular Culture and Media

Representation in Film and Literature

Ikebana appears throughout creative media as:

Plot Device – In films like “The Flower Arrangement” and “Late Spring” where ikebana becomes metaphor for characters’ emotional journeys.

Cultural Marker – Literary works using ikebana to establish authentic Japanese settings or character backgrounds.

Philosophical Framework – Essays and philosophical texts referencing ikebana principles as models for balanced living.

Notable literary references include Yasunari Kawabata’s writings Sawako Ariyoshi’s “The Twilight Years” and contemporary works like “The Goddess of Small Victories” where ikebana serves as recurring motif.

Crossword Puzzles and Word Games

The phrase “Japanese art of flower arranging” frequently appears in crossword puzzles including those published in The New York Times. Crossword enthusiasts encounter:

Common Clues

- “Japanese flower arrangement”

- “Artistic flower arrangement from Japan”

- “Floral art of Japan”

- “Traditional Japanese arrangement”

Expected Answers

- IKEBANA (7 letters)

- IKENOBO (7 letters – referring to the school)

- KADŌ (4 letters – alternate term meaning “way of flowers”)

These references in popular puzzles have introduced many to the term even if they lack familiarity with the actual practice.

Social Media and Digital Presence

Modern ikebana maintains vibrant online presence through:

Instagram Communities – Hashtags like #ikebana #ikebanainternational and #contemporaryikebana connecting global practitioners.

Virtual Exhibitions – Online galleries showcasing work from practitioners worldwide particularly valuable during recent pandemic restrictions.

Instructional YouTube Channels – Video tutorials from major schools and independent teachers democratizing access to instruction.

Digital Publications – Online magazines and blogs dedicated to contemporary interpretations and traditional practices.

This digital presence has revitalized interest among younger generations creating new pathways for ikebana’s continued evolution.

Environmental and Sustainability Considerations

Ecological Awareness in Modern Practice

Contemporary ikebana increasingly addresses environmental concerns:

Sustainable Harvesting – Ethical gathering practices for wild materials avoiding endangered species and respecting growth cycles.

Seasonal Locality – Using materials available locally during natural growth seasons rather than imported out-of-season flowers.

Longevity Focus – Creating arrangements with extended lifespans through proper technique and material selection reducing waste.

Floral Foam Alternatives – Developing and using biodegradable fixation methods avoiding petroleum-based floral foams.

Leading teachers increasingly emphasize these ecological dimensions viewing responsible material sourcing as essential aspect of respecting nature’s gifts.

Preservation of Traditional Knowledge

Efforts to document and preserve traditional ikebana knowledge include:

Historical Archives – Major schools maintaining records of arrangements teaching materials and lineage information.

Museum Collections – Specialized museums in Kyoto Tokyo and other cities preserving historical containers tools and documentation.

Living National Treasures – Government recognition of master practitioners as bearers of important cultural knowledge.

Digitization Projects – Converting historical manuals photographs and records to accessible digital formats.

These preservation efforts ensure that traditional knowledge remains available to future generations while allowing contemporary practitioners to innovate from solid foundation.

Therapeutic Applications of Ikebana

Mental Health and Mindfulness Benefits

Research increasingly supports ikebana’s psychological benefits:

Stress Reduction – Studies showing decreased cortisol levels and reduced anxiety after ikebana practice sessions.

Attentional Focus – Improved concentration capacities through regular practice requiring sustained attention.

Emotional Regulation – Enhanced mood stability through mindful engagement with natural materials.

Creative Expression – Providing outlet for non-verbal emotional processing through compositional choices.

Mental health professionals occasionally recommend ikebana as complementary practice for patients dealing with anxiety depression or attention disorders.

Physical Therapy Applications

Ikebana practice offers physical benefits particularly for:

Fine Motor Skills – Precise cutting positioning and manipulation of materials enhancing dexterity.

Hand-Eye Coordination – Activities requiring visual perception translated into physical movement.

Posture Awareness – Proper arrangement practice encouraging spine alignment and body awareness.

Breath Regulation – Focused work naturally encouraging slower deeper breathing patterns.

Some rehabilitation programs incorporate modified ikebana techniques for patients recovering from stroke hand injuries or neurological conditions affecting movement precision.

Community and Social Connection

Group ikebana practice fosters:

Intergenerational Bonding – Activities appropriate for participants of widely varying ages.

Cross-Cultural Communication – Shared creative practice bridging language and cultural differences.

Non-Verbal Expression – Meaningful interaction possible even for those with communication challenges.

Structured Social Engagement – Providing framework for interaction reducing anxiety for socially hesitant participants.

Community centers retirement homes and mental health programs increasingly offer ikebana classes specifically for their social connectivity benefits.

Ikebana Exhibitions and Competitions

Major International Events

The ikebana calendar features prestigious events including:

Ikebana International World Convention – Biennial gathering featuring exhibitions demonstrations and workshops from all major schools.

School-Specific Exhibitions – Major presentations by Ikenobo Sogetsu Ohara and other schools showcasing their distinctive approaches.

Museum Collaborations – Special exhibitions at institutions like Victoria and Albert Museum Boston Museum of Fine Arts and National Gallery of Victoria.

Botanical Garden Installations – Large-scale exhibitions at major botanical gardens worldwide highlighting seasonal themes.

These events typically combine public display with educational programming allowing both appreciation and deeper understanding.

Judging Criteria and Standards

Competitive ikebana evaluation considers:

Technical Execution – Proper cutting placement and structural integrity.

Creative Interpretation – Original expression while maintaining school-specific principles.

Material Selection – Appropriate choices for season theme and container.

Overall Impact – Emotional and aesthetic effect of completed arrangement.

Balance and Proportion – Successful relationship between elements container and space.

Judging methods vary by school with traditional schools often employing stricter technical criteria while contemporary venues may emphasize innovative approaches.

Exhibition Etiquette and Viewing Practices

Visitors to ikebana exhibitions should understand:

Viewing Distance – Standing approximately arm’s length from arrangements allowing proper perspective.

Viewing Angle – Observing from front position first then sides to appreciate three-dimensional qualities.

Quiet Contemplation – Maintaining reflective atmosphere allowing others to experience works without distraction.

Photography Policies – Respecting venue-specific rules regarding photography which may be restricted.

Attribution Awareness – Noting artist names and schools understanding that arrangements represent both personal expression and school traditions.

Business Aspects of Ikebana

Professional Opportunities

Ikebana training can lead to various professional paths:

Teaching – Certified instructors offering classes through cultural centers schools private studios and online platforms.

Commercial Installation – Creating arrangements for hotels restaurants corporate environments and retail spaces.

Event Design – Specializing in ikebana for weddings ceremonies corporate events and special occasions.

Therapeutic Practice – Working with healthcare facilities retirement communities and wellness programs.

Artistic Career – Developing exhibition-focused practice creating installation works and gallery pieces.

Professional practitioners typically combine multiple income streams adapting traditional practices to contemporary market demands.

The Economics of Materials and Tools

Establishing professional ikebana practice involves understanding:

Investment Considerations

- Quality tools (professional-grade scissors specialized hasami)

- Container collection (varying sizes styles materials)

- Storage and transportation equipment

- Studio space with proper lighting water access work surfaces

Ongoing Expenses

- Fresh materials (seasonal plants branches flowers)

- Maintenance supplies (kenzan cleaners preservatives)

- Transportation costs

- Marketing and promotion

- Professional development and continuing education

Pricing Structures

- Hourly rates ($75-200/hour depending on location experience)

- Per-arrangement pricing ($150-1000+ depending on size complexity venue)

- Class fees ($30-100 per student session)

- Subscription services (weekly/monthly arrangements for businesses)

Cultural Appropriation Considerations

Professional ikebana practitioners must navigate:

Respectful Practice – Acknowledging Japanese cultural origins while practicing authentically.

Proper Attribution – Crediting specific schools traditions and teachers rather than presenting ikebana as generic “foreign” art form.

Continuous Education – Ongoing study of cultural context historical background and philosophical foundations.

Representation Issues – Thoughtful presentation avoiding orientalist stereotypes or surface-level cultural borrowing.

Ethical practitioners maintain connection with traditional lineages seeking proper certification and authorization rather than simply adopting aesthetic elements without understanding underlying principles.

FAQs about Japanese Art of Flower arranging nyt

2 How long does it take to become proficient in ikebana?

Basic forms can be learned within several months of regular practice but true proficiency typically requires 3-5 years of consistent study. Mastery is considered a lifelong journey with many practitioners continuing to develop their skills over decades.

3 What are the essential tools needed to begin practicing ikebana?

Beginners need sharp floral scissors (hasami) a kenzan (needle holder) several simple containers a bucket for conditioning materials and access to fresh seasonal plant materials. Advanced practitioners gradually expand their container collections and specialized tools.

4 Can ikebana be practiced without formal instruction?

While basic principles can be self-taught through books and videos traditional schools emphasize the importance of direct instruction from certified teachers. Proper technique posture and approach are difficult to learn without personalized guidance and feedback.

5 Is ikebana only practiced by women?

Historically ikebana was primarily practiced by Buddhist monks and samurai warriors. Though women became the primary practitioners during the 20th century contemporary ikebana attracts practitioners of all genders with many leading teachers and headmasters being men.

6 How are ikebana arrangements preserved?

Ikebana arrangements are not typically preserved as their impermanence is considered philosophically important. However photographing arrangements provides documentation and certain techniques like drying preserving or pressing elements can extend arrangement lifespans.

7 What is the meaning of "kado" in relation to ikebana?

Kadō (華道) literally translates as "the way of flowers" emphasizing ikebana as spiritual discipline rather than merely decorative practice. This term parallels other Japanese cultural practices like sadō (tea ceremony) and shodō (calligraphy) that are considered paths to spiritual development.

8 How does seasonality affect ikebana practice?

Seasonality forms fundamental principle with arrangements expected to reflect current season through material selection. Using out-of-season materials traditionally considered inappropriate as arrangements should connect viewers to present moment and natural cycles.

9 Can artificial materials be used in ikebana?

Traditional schools generally discourage artificial materials though contemporary schools particularly Sogetsu embrace non-traditional elements. Beginners are typically advised to master natural materials before experimenting with artificial components.

10 How does ikebana appear in The New York Times crossword?

"Ikebana" and related terms appear regularly in The New York Times crossword puzzles typically clued as "Japanese art of flower arranging" "Floral art from Japan" or similar phrases. The term's regular appearance has made it familiar to puzzle enthusiasts worldwide.

Conclusion: The Continuing Relevance of Ikebana

Bridging Tradition and Innovation

Ikebana’s enduring appeal stems from its unique balance between:

Historical Continuity – Unbroken traditions dating back centuries providing solid foundation.

Adaptability – Capacity to incorporate new materials techniques and aesthetic approaches while maintaining core principles.

Cross-Cultural Dialogue – Serving as bridge between Japanese traditions and global artistic practices.

Philosophical Depth – Offering conceptual framework relevant to contemporary concerns about mindfulness sustainability and relationship with natural world.

This dynamic tension between preservation and innovation ensures ikebana remains living tradition rather than museum artifact.

Personal Growth Through Practice

Beyond aesthetic outcomes dedicated ikebana practice fosters:

Patience – Developing capacity to work methodically with attention to detail.

Observation Skills – Heightened awareness of natural forms patterns and relationships.

Acceptance of Impermanence – Understanding beauty’s transient nature as arrangements inevitably fade.

Environmental Consciousness – Deepened appreciation for seasonal cycles and ecological relationships.

Cultural Appreciation – Gateway to broader understanding of Japanese aesthetic principles and cultural values.

Many long-term practitioners report that these secondary benefits ultimately prove more significant than the arrangements themselves.

Future Directions and Possibilities

Looking forward ikebana continues evolving through:

Technological Integration – Virtual reality platforms allowing remote collaboration and instruction across distances.

Scientific Partnership – Collaboration with botanical researchers developing sustainable harvesting techniques and plant preservation methods.

Architectural Applications – Influencing built environment design through concepts of negative space asymmetrical balance and naturalistic forms.

Environmental Activism – Practitioners advocating for plant conservation habitat preservation and sustainable horticultural practices.

Cross-Disciplinary Exploration – Dialogue with contemporary art performance installation and digital media expanding expressive possibilities.

As global interest in mindfulness practices environmental consciousness and Japanese culture continues growing ikebana remains perfectly positioned at this cultural intersection offering both aesthetic pleasure and deeper philosophical engagement.

Pingback: Japanese Nail Art | Traditions and Trends